Introduction

In painting, creating a convincing sense of depth relies on understanding how objects change as they recede into the distance. Two key factors in this illusion are contrast and color saturation. By observing how light and atmosphere affect visibility, artists can replicate these effects to enhance realism and three-dimensionality in their work.

This guide explores:

- The science behind contrast and distance

- The role of atmospheric perspective

- How color temperature and saturation shift with distance

- Composition techniques to reinforce depth

- Practical applications in different painting styles

1. The Science of Contrast and Distance

Why Do Nearby Objects Have Stronger Contrast?

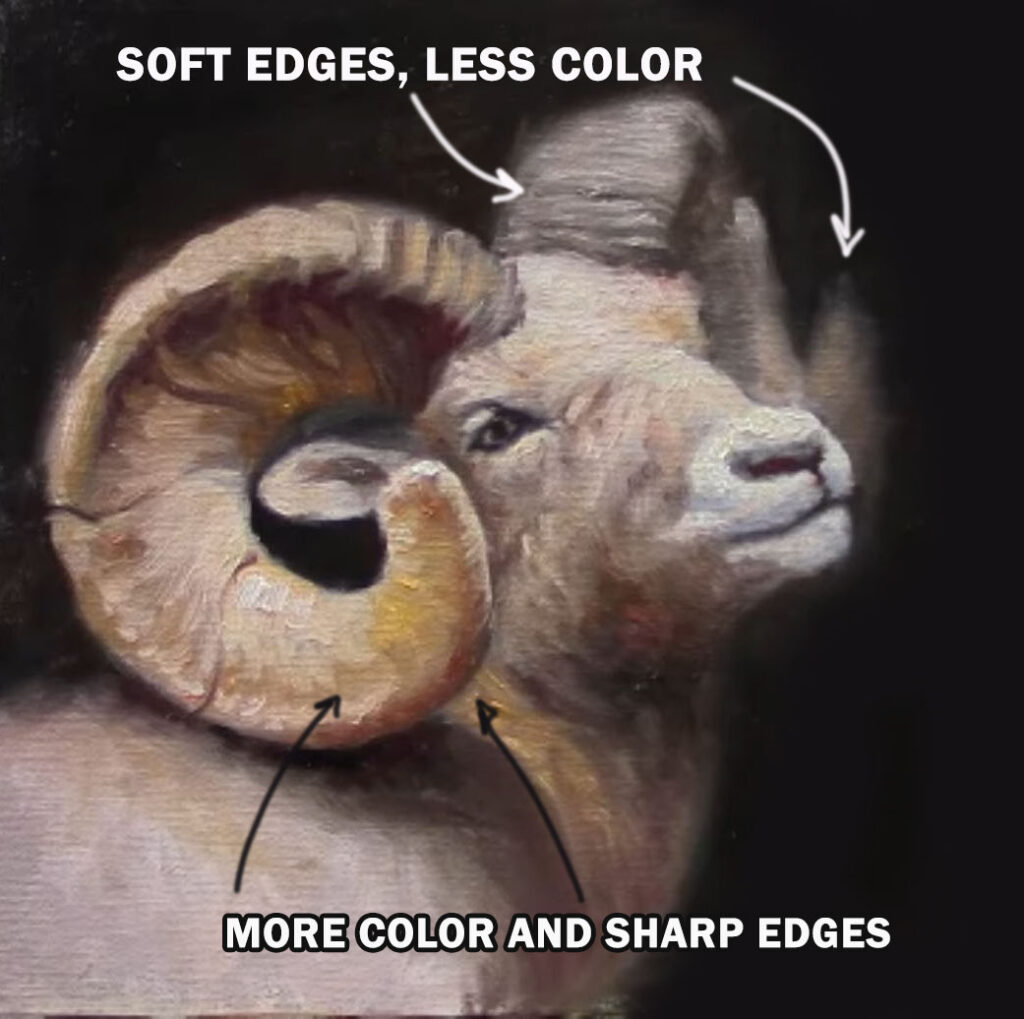

When an object is close to the viewer:

- Shadows are darker and more defined (due to direct, undiffused light).

- Highlights are sharper (reflections appear more concentrated).

- Edges remain crisp (less atmospheric interference).

As objects move further away:

- Contrast decreases (shadows lighten, highlights soften).

- Details blur (edges become less distinct).

- Textures fade (fine lines and surface imperfections disappear).

This phenomenon occurs because light scatters as it travels through air, blending shadows and highlights into midtones.

Atmospheric Perspective (Aerial Perspective)

Leonardo da Vinci was among the first to study atmospheric perspective, noting that distant landscapes appear:

- Lighter in value (due to scattered light).

- Bluer or grayer (because short-wavelength blue light disperses more).

- Less detailed (particles in the air act like a soft-focus filter).

This effect is strongest in:

- Landscapes (mountains, forests, skies).

- Urban scenes (distant buildings fade into haze).

- Seascapes (horizon lines blend with the sky).

2. How Color Changes with Distance

Color Saturation and Value Shifts

- Nearby objects:

- Colors are more saturated (vivid and intense).

- Warmer hues (reds, oranges, yellows) dominate.

- Shadows retain their local color (e.g., a red apple keeps its deep red shadows).

- Distant objects:

- Colors become desaturated (muted, milky, or grayish).

- Cool tones (blues, purples) dominate due to Rayleigh scattering (the same effect that makes the sky blue).

- Shadows lose their chromatic intensity, blending into the ambient light.

Practical Applications

- Landscape painters often glaze distant hills with thin, cool layers.

- Portrait artists soften background edges to push them back in space.

- Still life painters use warmer, richer colors in foreground objects.

3. Composition and Depth Cues

Positioning Objects for Depth

Our brains interpret depth based on placement:

- Lower in the frame = closer (we perceive objects near the bottom as being in front).

- Higher in the frame = farther (distant objects appear elevated, like mountains).

Additional Depth Cues

- Overlapping forms – An object blocking another reinforces spatial order.

- Size scaling – Smaller objects appear further away.

- Linear perspective – Converging lines (e.g., roads, buildings) enhance depth.

4. Applying These Principles in Different Painting Styles

Realism & Traditional Painting

- Glazing techniques build atmospheric haze in layers.

- Soft vs. hard edges separate foreground from background.

- Temperature contrast (warm foreground vs. cool background).

Impressionism & Expressive Painting

- Broken color (using separate brushstrokes for distant vs. near elements).

- Exaggerated color shifts (e.g., Monet’s use of violet shadows in faraway objects).

Digital & Concept Art

- Depth layers (foreground = high contrast, midground = moderate, background = low).

- Blur effects (simulating depth of field).

5. Common Mistakes & How to Fix Them

❌ Problem: A painting looks flat because all objects have the same contrast.

✅ Solution: Increase foreground contrast, reduce background contrast.

❌ Problem: Colors appear unnatural in distant objects.

✅ Solution: Introduce subtle blue/gray tints to faraway elements.

❌ Problem: The composition lacks depth despite correct values.

✅ Solution: Use overlapping shapes and size variation.

Conclusion

Mastering the relationship between distance and contrast is essential for creating believable depth in art. By observing nature and applying principles of atmospheric perspective, color shifts, and compositional depth cues, artists can produce more dynamic and realistic paintings.

Further Study

- Study J.M.W. Turner’s landscapes for masterful atmospheric effects.

- Experiment with limited palettes to force depth through temperature shifts.

- Practice monochromatic studies focusing solely on value contrast.

“You can support my art journey for free by shopping art supplies through my Amazon store—thanks a ton!”: https://www.amazon.com/shop/rensoart

- Adding Colors You Do Not See in the Picture to Create a Different Mood

- Are You Using Too Much Paint as a Beginner?

- How AI Can Sharpen Your Blurry Photos

- The Artistic Principle of Transparent Shadows and Opaque Lights in Oil Painting

- Choosing the Right Brushes for Oil Painting